Phase transition

Positioning means displacing something… It might be a direct competitor, indirect competition, or established medical practice, but something somewhere has to be edged aside for your product to fit into a future landscape.

Two kinds of phase transition problem impact innovation in pharma. The first, perhaps one of the biggest single killers of innovation: the emphasis on phase transition rates in Development. Groups organised to simply get from phase I to phase II or from phase II to III have a perverse incentive structure. To create a truly agile or innovative organisation would mean breaking that paradigm. (I wrote more on that challenge here…)

The second is a failure-to-plan that impacts launch.

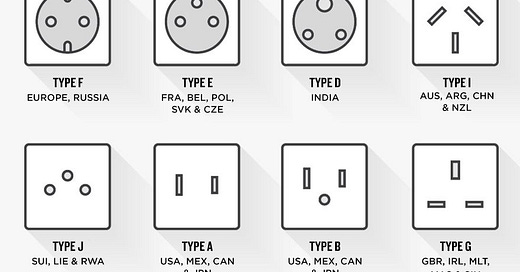

As an analogy, while we can all imagine that the world would be better off with a single design of power socket, the phase between then and now is almost unimaginable (for South Park fans, this is known as the ‘underpants gnomes’ problem: ‘collect underpants - something - profit’, where ‘something’ is undefined). It is uncrossable territory, as there is too much to change. It almost doesn’t matter how much you plan your two states, your ‘as is’ and ‘to be’ - the magical world it could be if everything changed overnight. Shifting the user base is not going to happen because the gain (to them) is less than the hassle. Imagine being forced to change all the sockets in your house, or your business, because someone decided the UK plug was the standard for safety, reliability and more.

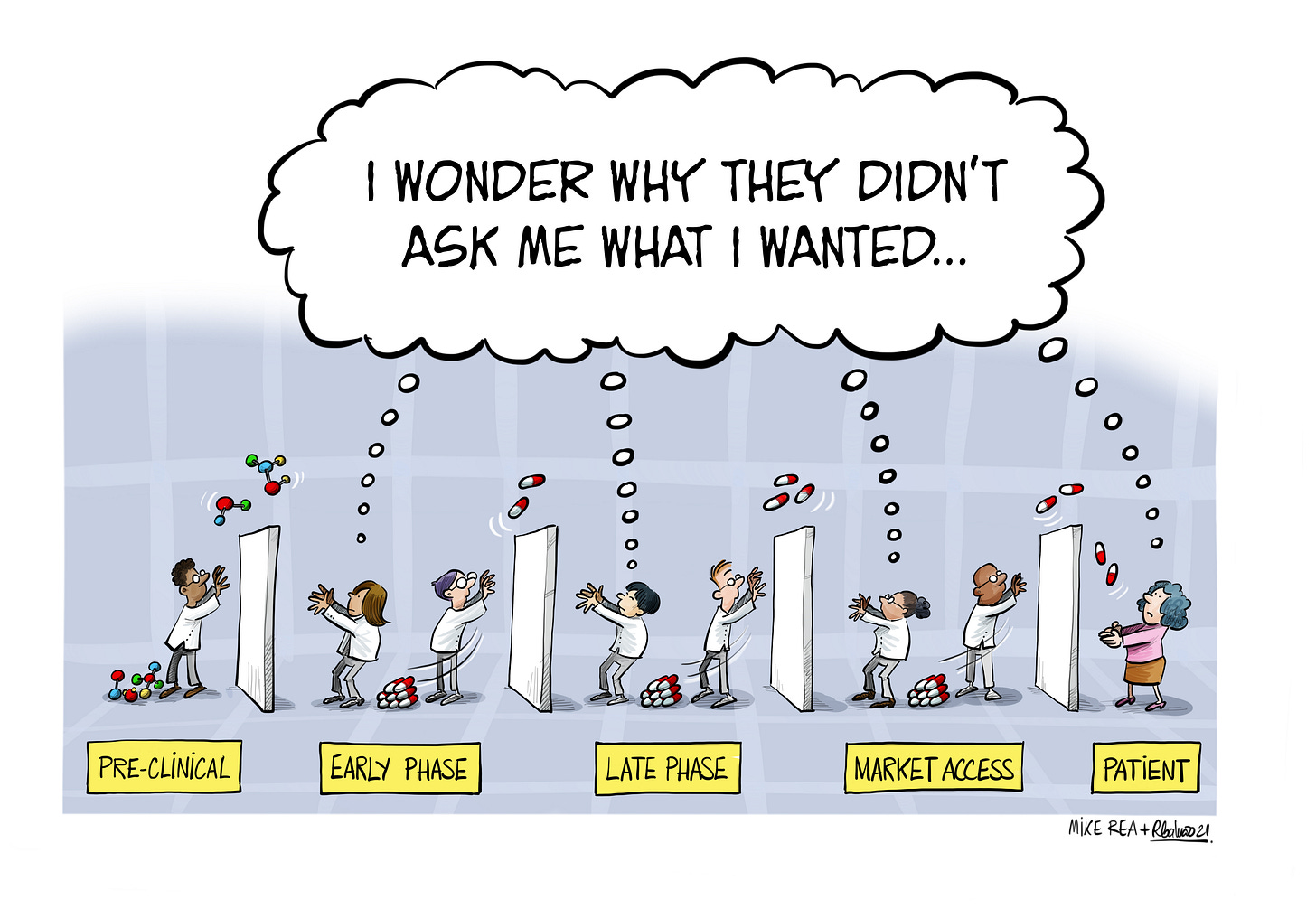

Pharma misses this challenge when it launches cell and gene therapies, or new classes more broadly - it often presents the ‘to be’ data as compelling enough to change practice, but forgets the practicalities of shifting the user base. There are many ways in which clinical studies are unlike the real world, but the motivations of investigators rarely track to the complexities of real physicians and real patients (and their very real payer systems).

If I want my gene therapy, for example, to succeed in a world in which you, the prescriber, today have a perfectly viable enzyme replacement therapy, I need to do more than just provide an equivalent outcome over 4 years at an equivalent cost, on a standard measure. This has been true of PCSK9s vs statins, novel heart failure medicines over standards of care, and more. It’s particularly true of cell and gene therapies, which on the surface seem magical, but encounter real-world logistics and economic problems.

The user experience of the installed base matters - and the user experience is more than simply ‘prescribe and watch’. The day 0 experience (deciding, prescribing, getting it paid for), the day 1 experience (watching for some form of outcome, seeing how the patient is doing), the day 30 experience (is it different in any way?), etc., all matter. How much does the prescriber get paid to do what they did yesterday vs what they’ll get paid now? How much does their comfort with established practice factor in when there’s a totally novel approach to learn? What does the patient experience that they wouldn’t have experienced with the previous gold standard?

In my cartoon, this traditional linear ‘think about the user later’ approach is lampooned - everyone recognises this pattern, but if patients, physicians and payers are thought about too late, the risk of delivering something they don’t want, or that doesn’t fit, is high.

Your technology may well be better, on paper. But prescriptions aren’t written on paper - they’re written in the minds of the prescriber, and the better you understand their experience, the more likely you are to launch a successful alternative. Too much time on the data, and not enough on the practicalities, can kill great medicines.

Unfortunately this problem can find its source back in the first problem of phase transition. Science can win at each phase transition until approval, when real user experience takes over. A programme that wasn’t designed against the end user experience (value endpoints, duration, ease of application, economics and more) will then have an army of sales, medical affairs and more trying to force fit it into a real world application.

Many companies that think of themselves as ‘learning organisations’ miss this problem, preferring their learning to be linear. ‘If we take care of the science, the rest will take care of itself’ is a way to avoid positioning in early phase, but just creates problems for later.

Data that are easy to collect may be at odds with, or insufficient for, evidence that will effect a phase transition in the market. Ironically, data that are easy to collect continue to drive the phase transition rate problem in more established pharma companies - for as long as it’s easy, and you are rewarded for simply moving from phase II to phase III, it’s hard to shift to a more productive system. Your positioning may require endpoints that need to be validated in phase II in order that they can be part of your phase III, and therefore your label, or patient identification/ stratification that needed to be part of a pre-planned approach. Wishing that you’d had those endpoints at any point after the start of phase II is too late, but it happens every day.

The evidence that may make a physician move away from familiar territory to unfamiliar practice is unlikely to sit simply in the Kaplan-Meier curves. Recognising the real world in which decisions are made is the starting point. Even for an index patient, all the pros and cons of a new kind of decision need to be understood and planned for. So many great drugs fall down for their failure to predict established behaviour’s response to a request for change. If you’d have reasons not to change your power sockets (network voltage, service providers, difficulty in finding parts, appliances that would not fit, etc.), all of those reasons and more can be found in a new drug or modality. So, your positioning can’t be ‘this would be better, but we recognise you have to change your practice…’. Anticipating what needs to change, and how to help people transition, is critical.