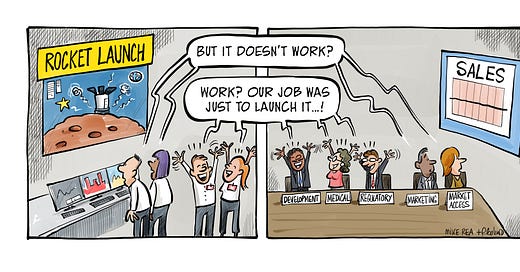

What is at the core of our biggest challenge in pharma? We develop and present ‘false world’ data on our drug to regulators, payers and prescribers, who then try to gauge how best to release it into their real world.

The task of positioning is to find a place in the real world for our medicines, but the route to that point is via a series of ‘false world’ studies. This article is not about the validity of that approach, but to recognise the challenge of positioning in this situation.

The ‘place in the mind of our customer’ goal when positioning pharmaceuticals is a place firmly embedded in the real world: of direct and indirect competitor treatments, of imperfect diagnoses and real, messy patients, of cost, value and incentives. This reinforces, more than anything else, the need to not treat messaging and positioning as in any way interchangeable. In ethical pharma, you can say (only) what you have proved, and if all you have proved is your drug’s place in a false, sterile world setting, then the challenge of communicating value in the real world is made harder, by design, and by choice.

Your task, when positioning drugs, is to position for the real world: to provide a direction for Development, to specify data to collect, to decide what you want to be able to claim in the future. The passive approach can only ever reflect a false world view, however nicely packaged the story looks. This active look forward is critical to launching a drug that works when it lands.

Find the pathway

Integrating “real worldness” into the drug development process can be challenging and complex, with a plethora of decisions to make along the way. In the past, pharma has tended to opt for lowest technical risk on the way to regulatory approval which leads to presenting “false world” data to the market at time of launch. This means two things: that real world evidence is often added as an afterthought, and that our messaging can only reflect what we studied. Unfortunately, even the advances made in incorporating comparative effectiveness considerations into the mix leads to challenges. For example, is the standard of care the same in every region?

“Prescribers want to see that the manufacturer knows this stuff, because it matters to them. Unfortunately, many manufacturers want to do as little of this as possible”

Finding the ideal place for a new drug, both in reality and in perception, is the key focus for positioning and this is where real world evidence comes into its own. Presenting an opportunity to understand how best to use a drug in a regimen, in sequence, in severity of disease, line of therapy, etc., and with what concomitant medications.

The industry needs to understand what part of “reality” it wants to evaluate. So whilst it is critical in the pharmaceutical development pathway to obtain “clean” perspectives of what impact a drug has, the industry is essentially leaving patients with fewer options than ideal. For example, it is estimated somewhere around 90 per cent of people living with depression would not qualify for a clinical trial into an anti-depressant, simply because they are too complicated. So, as well as reviewing ways that pharma could look at 'all comers' in development studies, it is critical to also look into techniques to evaluate the data that would produce.

Strengthen existing development strategies

Some in the pharma industry have questioned the need to include real world evidence in a regulatory submission. Planning for further evaluation should be a key part of the mix.

“It is unusual, for example, for companies to be able to pool data from phase II and phase III because of the way those data are collected. Even making this step would be helpful for prescribers”.

In addition, rolling studies on, instead of doing the bare minimum, would be helpful as well. We have seen people deliberately stop trials at six months or 12 months because they believe the effect of their drug will wear off after that - that is the kind of thinking that we could all agree we’d like to see die out. Most patients would be keen to know if a drug ‘wears off’ after 12 months.

With the rise in availability of generic products, among a range of other options patients now have access to, the essential reimbursement hurdle is changing the ways pharma thinks about development. Many companies are starting to realise the need to demonstrate the value of their product against everything else that is available to prescribers. Considerations of real world evidence can kill two birds with one stone.

Another factor to add to this mix is that the difference between the molecule and the product will become increasingly apparent to pharma. The molecule is fixed, but decisions on regimen, device, companion diagnostics, dose, etc., can all contribute to better adherence, tolerability and fitness for purpose of the medicine. There is a massive opportunity to make drugs more effective simply by altering some of these parameters: If pharma paid as much attention to this side of its business as it does to trying to find new molecules, that could make that same difference to effectiveness. This could potentially add a whole host of innovation to the process.

Seize the opportunity

Pharma companies generally want to create a competitive advantage, whilst prescribers are interested in understanding exactly how and in what ways a new drug will benefit their patients. Instead of companies launching drugs that only beat placebo, and whose effects as part of a treatment strategy are unknown, some companies are looking to be more patient-centric: That means real people, in real world scenarios, with real diseases. Incremental advances are one thing, but companies who preach right patient, right drug, right time have to start to deliver on that message.

A key part of real world evidence is companies actually being interested in what happens to their drugs once they are on the market and being used by patients on an on-going basis. In addition, new devices, diagnostics and other aids to patient management have to start to be considered early in development, rather than as afterthoughts.

A bright future

Imagine, for example, that pharmacovigilance, instead of being a 'necessary evil' was to become an opportunity to constantly monitor drugs in the real world. Whilst pharma might be worried to learn that their drugs are less effective than they want, they may in fact learn the opposite.

There will be key steps taken by some in the industry to simply integrate their activities, so more pooling of data can be done, leading to better statistical assessment of where a drug works, and where it doesn't. Apart from that, greater willingness to explore the possibility of segmentation - finding those patients who don't need the drug, or who don't benefit, rather than trying to pretend it works in everyone. Essentially this means we are likely to see less averaging of populations and more willingness to pre-specify sub-populations.

We can either continue to develop drugs for a false world, and provide evidence of how our drugs work there, or we start to realise the reality of our customers' lives and deliver products that meet those needs.